Dornoch Airstrip - rabbit clearance

Date Added: 24 February 2012

Year: 1972

Institution Name: dnhhl

Cat No: ◀ | 2010_053_44 | ▶

Picture No: 10916

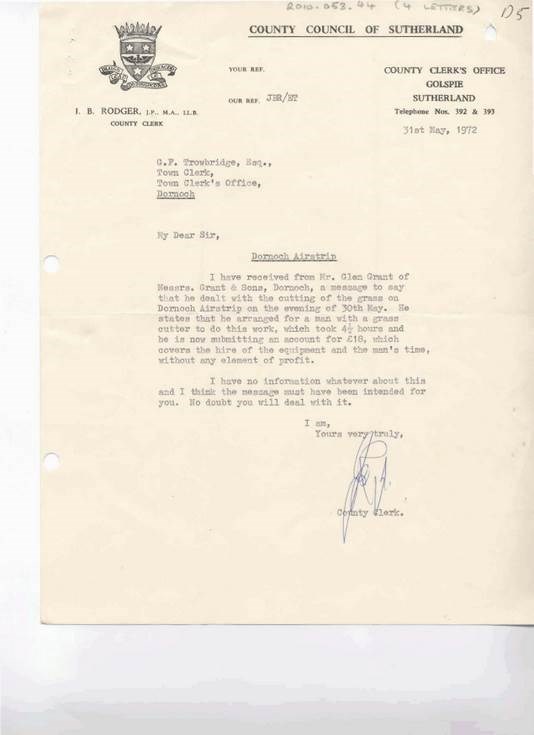

Four letters relating to grass cutting and rabbit clearance.

Dimensions: pdf file

1 Comment

Form Goes Here

These letters telling of the rabbit problem at the Dornoch airstrip reminded me of rabbit hunting in Embo, during and just after World War 2. I am not being strictly correct in calling it 'rabbit hunting' because in Embo we always called it 'rabbit poaching'. This was strange, because in most instances it was not even poaching at all.

The Ground Game Act of 1880 gave landowners, for the first time, the right to hunt and kill rabbits on their own land, and the right to give their permission to others to do the same. To my knowledge farmers whose lands were adjacent to Embo did not formally give permission to villagers the right to hunt rabbits on their land. However, they did condone it, as they accepted that rabbits were in stiff competition with their sheep for available grazing. It was claimed away back then that ten to twelve rabbits ate as much grass as one sheep, and I have seen on the Web that recent scientific research in Australia and New Zealand has confirmed these figures. But however, these farmers would very angrily come down hard on any rabbit hunters who damaged their crops or farm infrastructure while hunting, or those who allowed their dogs to worry their sheep or other livestock.

In our rabbit 'poaching' efforts we used three methods, all of which had their respective pros and cons. These were by the use of ferrets, snares, and dogs. I as a young boy was an enthusiast of all these three but I have to admit that ferreting was my favourite. Not only because I believed it to be the most efficient and rewarding in getting plenty of meat on the table, but it also allowed one to have the additional pleasurable experience of keeping ferrets as pets.

But caution was needed in this regard as a ferret that became too much of a pet often forgot that he was first and foremost a working ferret.

The ferrets we used in Embo for hunting rabbits were for the most part white in colour, but grey and mottled black and white ones were also used. White ferrets were preferred for hunting rabbits as they were more easily found if they wandered away and got lost during the hunt. This often happened when a burrow in a rabbit warren or set that was mistakenly, for whatever reason, not blocked by a purse net.

Of course all ferrets had their own personalities, just like people. Some were lazy, some were stupid and easily outwitted by rabbits, some were eager to please and some were grumpy and mean spirited and some were always hungry. For that very reason trading in ferrets was always part of the ferret keeping fraternity's tradition.

The art of successful hunting with ferrets required the hunter to have a detailed knowledge of where rabbits were plentiful and healthy and also knowing where they were lawfully allowed to hunt. Or where, if not lawfully permitted, where they could hunt undetected! Luckily in the near vicinity of Embo there were plenty of 'legal'hunting areas. These were the commonage areas that stretched from the land seaward of the Dornoch/Mound railway line at the Dornoch Golf course ninth green and below Geordie aigh Sara's farm at Embo Street. Then to the North past the 'back park' then over the Cluen river and right along the 'plains' below Coull Farm until the shore of Loch Fleet as far as Skelbo Castle. Of course we always referred to Loch Fleet as the 'The Little Ferry'.

All hunters had their favourite hunting places which they often tried to keep secret from others. Some more adventurous hunters hunted in the area inland from the 'Crossroads'. Actually, although always known as the 'Crossroads' this was in fact a 'T' junction, with one road going South to Dornoch, one going North to Fourpenny and one going seawards to Embo. I was part of a group that hunted in this area but it was more suitable for using snares as the Forestry Commission had fenced large parts of the area, and many gaps in these fences cried out for a snare.

But I am jumping the gun and will get on to snaring in a moment.

Hunting with ferrets was done during late autumn and winter so the hunters had to be hardy and prepared to brave long periods out in the cold. These months are outside of the rabbits normal breeding season and because of this pregnant and lactating does, and their bunnies were not met up with. Ferreting cannot be done successfully during the breeding season as lactating females will not bolt, and bunnies cannot, when confronted with a ferret, and there was also a taboo against hunting or killing them. They were certainly never eaten.

The ferreting equipment used was simply a number of homemade purse nets with their securing wooden pegs tied to them with a short length of stout rope, a garden spade, and of course a well trained ferret. Some hunters used to carry a hammer for knocking the purse nets wooden pegs firmly into the ground, but mostly a decent sized stone gathered on the way was sufficient for this task. Normally dogs would accompany the hunters and they were useful in making rabbits above ground seek the safety of their burrows, and of course thus indicating which warrens were then in use. Once an occupied warren was identified all its individual burrows would be fully covered with a purse net that was properly secured to the ground with its rope and wooden peg.

The making of purse nets by Embo men was a simple matter as they relied on their extensive fishing and sailing skills with nets, ropes and knots. The items they needed for this task was a supply of strong twine, a largish steel key ring to gather all the netting to one point, an 8 inch purse net needle, and a mesh measuring stick to keep all the mesh holes to the same size. When the net was complete a wooden peg was tied to the key ring with a plaited length of twine to allow the net to be firmly anchored in the ground when in use.

The ferret would then be introduced into the warren via one of its burrows and then silence would be maintained. Any noise at this stage had the effect of making the rabbits hesitant to bolt from the warren and this led to the risk of them being caught, killed and then eaten by the ferret. In such a situation the spade came into use to dig out the ferret and the rabbit. If that failed to recover the ferret all the warrens burrows were blocked with stones and soil and the hunt abandoned while daily checks were made on the warren until the now hungry ferret was recovered. It is a sad fact that ferrets, like grumpy old men, like a sleep after a good meal.

I remember several such recoveries of ferrets, and they always came out of the unblocked burrow blinking in the day light, and with a facial expression which seemed to be asking what was all the fuss was about. Of course such problems are not experienced by todays ferreters as they have access to electronic locators which work in conjunction with miniature electronic transmitters tied to their ferrets collars.

A well planned, researched and executed ferreting hunt could yield up to ten healthy and very eatable rabbits. These rabbits were always dispatched humanely and any unnecessary suffering on the part of the rabbit was always avoided.

Hunting rabbits by the use of snares was usually done by a hunter working alone. Here again there were many skills needed for a successful hunt. First of all the snares were normally made by the hunter himself. These were made of a strong springy braided brass wire and a sturdy brass eyelet. These were bought at Leonard Wills general dealers shop in the High Street in Dornoch. The brass wire was made into a loop by being run through the eyelet and the free end firmly secured to a sturdy rope which in turn was tied to a wooden peg. The area to be hunted was then checked for where rabbits moved along 'beats' or runs.

The snare was then placed so that a rabbit moving on such beats would be caught in the snare. The art was to place the snare in such a position to ensure that the rabbit would be snared without it being spooked or made cautious by anything unusual. The snare loop was kept in the correct position and height by the use of a small forked stick that we called a 'geeban in Gaelic which I now know is called a tealer in English.

Up to twenty snares were set and then left for usually a 24 hour period and then checked on and any rabbits caught collected and the snares reset, or if necessary moved to a new location.

The hunting of rabbits with dogs was also done. An intelligent and well trained hunting dog, along with a hunter with similar qualities, were necessary for a successful hunt. It also goes without saying that an area where healthy rabbits were plentiful and without too much vegetation were also necessary. Too dense vegetation gave rabbits too big an advantage as they used such vegetation to change direction and speed quickly and outwit and tire the dog and then escape. The hunter had to always assist the running dog by herding the running rabbit back into the path of the dog. This was done by blocking of the rabbits escape path by quick runs, shouts and whistles and also arm waving. Some of the older boys were very proud of their hunting dogs and they themselves were famous for their hunting exploits.

Their dogs they treated with great affection and care. Some of these older boys were expert at throwing a wooden staff parallel with the ground at the running rabbit causing it to stumble and fall allowing their dog to catch and secure the rabbit. I remember that my late oldest brother 'Donnie James' Mackay and my brother James William (Hamish) Mackay and their friends James and Thomas Grant had these skills. [James and Thomas were known in Embo and Jima and Toma and they were the sons of Alexander (Alex aigh Johan) and Isabella Grant (Bella aigh Deddle) and they lived at 3 Front Street].

All these hunting dogs had their own Gaelic names. One very popular such name was 'leas', which in English was faithful. Our family hunting dog was called 'ram' which a friend with more of the Gaelic than I advised that in English this name can mean 'devout', but it can also mean 'care', with 'ramach' meaning 'careful'. Yet again my young brother George Mackay advised that the word may have been 'cuirm', which translated into English means a 'feast' or 'banquet'. Why our dog could have been given this name I do not know, but perhaps it had something to do with its skill in providing a plentiful supply of rabbit meat for the table!

Sadly all these rabbit hunting exploits came to an end with the arrival of the rabbit disease Myxomatosis in the summer of 1953. Reports that we then got were that the disease was somehow man-made in Australia to rid that country of their feral European rabbit problem. The disease was then imported into the South of England to control a local rabbit pest problem, and from there quickly worked its way North to Scotland.

That summer I worked at the Forestry Commission tree nursery at Embo Street as a weeder with many other Embo early teenagers. We walked to and from work every day along the Dornoch/The Mound rail line and then up through Geordie aigh Sara fields and then to Embo Street, and all we ever then encountered were dead rabbits or rabbits obviously suffering from that disease.

The visible symptoms of the disease were eyes that were closed with crusted discharges and they also had snotty running noses, and of course such rabbits staggered about as if in a daze. Later virtually the whole of the rabbit population was wiped out. In later years there were reports that the effects of the Myxomatosis disease had waned and that some rabbits had developed immunity to it.

However, even on recent visits to Embo and the surrounding area I was always struck by the virtual absence of rabbits certainly ones that I would consider healthy enough to hunt and put on the table for a meal.

Some may be interested in learning how such rabbits were prepared for the table. In my recollection we always made the rabbit meat into a thick stew with plenty of any vegetables that were then available. First of all the rabbit had to be gutted and skinned and then the meat cut into largish portions. The most popular meat portion was that part of the back with the fillets on either side. The meat was then washed and partly dried and then dusted with a generous mixture of plain flour, salt and pepper.

Several chopped onions were then fried in lard in a pot and when they were golden brown the meat was then added and also fried until they too were well browned and crispy. Chopped vegetables and a very generous portion of chopped potatoes were then added along with some water and all cooked over a slow heat until all the meat and vegetables were cooked. The stew was then served from a large serving platter that we called an sher, placed at the centre of the table along with a large supply of boiled cabbage or Brussels sprouts. Stewed coinean was always a favourite. Delicious!

I have to tell that when rabbits were plentiful my father, William Mackay, known in Embo as 'Willie M' to distinguish him from the very many other William Mackays living there, often posted three rabbits at a time to his widowed sister Lucy Mackay and her three young sons in Glasgow. These sons were Kenneth Mackay (Kenny aigh Lula), William Mackay (Willie James) and Thomas Mackay (Tommy aigh Lula). Lucy was known in Embo as Lula.

Her husband, a Thomas Mackay, from 13 Back Street, Embo died on the 09/11/1934 from peritonitis following a ruptured appendix, when serving on the merchant ship SS Gregalia as its bosun on its way from Glasgow to Montreal in Canada.

Preparing the rabbits for posting was a simple matter. They were gutted and their fur was left in place. All three were then tied together with a stout string round their middle parts and then a thick brown paper was wrapped round their middles and secured with more string. The Glasgow address was then written clearly on the brown paper and one of us children then took the parcel to Katie Ross at the Embo Post Office and two days later the rabbits were enjoyed in Glasgow.

Can you imagine in this day and age trying to send such rabbits through the Post?

Sometime I must also tell of how we Embo boys and young men hunted for flounders, or what we called 'flukies' in the tidal pools of Loch Fleet. What was interesting was that we did not use hooks or lines but hand held spear like iron rods. Of course that was long before Loch Fleet was declared to be a bird and fish sanctuary in a National Nature Reserve!

Comment left on 20 July 2015 at 22:50 by Kenneth Mackay An interesting and entertaining social history comment Administrator